We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

A woodworking vise, according to its dictionary definition, consists of two jaws for holding work and a mechanism, usually a screw device, that opens and closes those jaws. That’s a rather broad definition, but then vises are a rather diverse lot.

For convenience, vises are loosely categorized by the position on the woodworking bench they usually assume. Vises of a design suited for the right-hand end or “tail” of the bench are of a rather different shape from those typically found attached to the front or “face” of the bench. Yet, as is true with most tools with long histories, not all vises fit neatly into simple subdivisions.

You see, some of the vises attached to the front of workbenches aren’t truly face vises, like the leg vise and shoulder vise. And the engineer’s vise traditionally is set neither on the face nor on the tail of the bench, but actually on the benchtop.

The bottom line? Most woodworkers will find a face vise invaluable; almost as many would quickly learn to love the advantages of a tail vise if they don’t already. The sturdy engineer’s vise is essential for anyone who works with metal—which includes almost every woodworker, by the way, when it comes to sharpening, and dealing with all sorts of hardware and other components.

Each vise has some specialized advantages, but you’ll have to make the call. And speaking of making, you’re luckier than your ancestors only a century or so ago. There are many kinds of vises in a myriad sizes on the market today. If you wish, you can make your own but, unlike your great-great ancestors, you don’t have to.

The Face Vise

Face vises are designed specifically for holding wooden workpieces while such operations as drilling and sawing are performed.

The traditional material is wood. A wood face vise consists of a movable front jaw that is mounted to a broad, square beam that slides in and out of a matching channel. While the beam keeps the jaw steady and properly aligned, the jaw is driven by a wooden bench screw. The whole mechanism is fastened to the benchtop from below.

Modern variations of the wooden face vise are often called woodworker’s vises. Also mounted flush to the bench front, these are all metal (except for jaw liners of wood that prevent the damage that would result if the metal jaws were tightened directly onto wooden workpieces.

Woodworker’s vises are designed to be attached to the underside of the front of a woodworking bench. The vise’s constituent parts include a pair of iron jaws, while its other components—its slides, drive, screw, and handle—are usually steel. Like wooden face vises, the inner jaw is fixed, while the outer jaw is operated by turning the handle centered on the front of the tool. Clockwise motion will tighten the screw mechanism, drawing the jaws together; a counterclockwise motion will open the jaws. These vises are usually located over or near a leg (to avoid putting unnecessary force on the benchtop) and are fastened with lag screws or carriage bolts.

Hybrid face vises combining wooden and metal elements are sold, and many woodworkers who elect to make their own benches fabricate matching vises, often using a mix of off-the-shelf metal drive elements with shop-made wooden jaws and attaching points such as blocking and guides.

Woodworker’s vises come in almost any size, with jaws ranging from six inches wide to ten inches or more, with a maximum opening capacity ranging from roughly four to as many as fifteen or more inches. The size you need depends upon the size of the stock you will be likely to use for most of your projects.

If you elect to buy a factory-made woodworker’s vise, you will probably need to line the jaws in order to protect your workpieces from the mars and dents that unlined iron jaws will cause when clamping wooden workpieces. To do so, affix jaw liners through the holes provided in the face of each jaw. The liners should be of nominal one-by stock (actual thickness, three quarters of an inch). If you work exclusively with softwoods, pine liners will suffice. However, you may wish to use a more durable hardwood liner.

The front jaw probably has threaded holes designed to accommodate flathead machine screws; you will need to countersink the screwheads so that they are set slightly into the wood liner. You can use wood screws driven from the face of the inner jaw into the face of the workbench.

The End Vise

Built into the end of a bench (almost always the right-hand end), the end or tail vise, as it is also called, can be used to clamp workpieces to the bench between its jaws. The flush-mounted end vise uses the benchtop as the inside jaw, and the bench screw drives the movable jaw tight against it.

The end vise is a much more flexible tool than might at first appear. It is distinguished from other vises in that a rectangular hole is cut into its top, and that hole is aligned with a series of other holes along the front of the benchtop. A workpiece to be shaped or cut is set along the front of the bench, flush to a bench dog set into the “dog-hole” in the vise. The other end of the piece is then butted to another dog inserted through the dog-hole nearest to it and quicker than you can say, “Tighten her up,” the tail vise transforms virtually the entire benchtop into a giant vise. For that reason, the tail vise, with its ability to hold work between bench dogs, is one of the hallmarks of a cabinetmaker’s bench.

The Leg Vise

This antique vise was probably an American innovation. Today, it’s relatively rare, having been largely superseded by the woodworker’s vise. That doesn’t mean it isn’t a worthy tool; on the contrary, it’s a simple, strong device that is probably the easiest of vises to make from scratch.

Usually set onto the front left-hand end of the bench, the leg vise has long jaws, the rear one, most often, being the leg of the bench. The outside jaw is the one that moves, and it is generally made ol large-dimension hardwood stock. A screwdrive, located above the midpoint of the vise’s length but below the area of the damping surface, adjusts the opening of the jaws. Occasionally, the bottom of the outside jaw is merely hinged to the bench leg, but this means that the jaws of the vise will not be parallel (except when closed), and the thicker the stock, the weaker the bite of the jaw. To avoid weakening what is otherwise a very efficient design, most leg vises have an adjustable screw or beam at the foot that keeps the jaws parallel.

The Engineer’s Vise

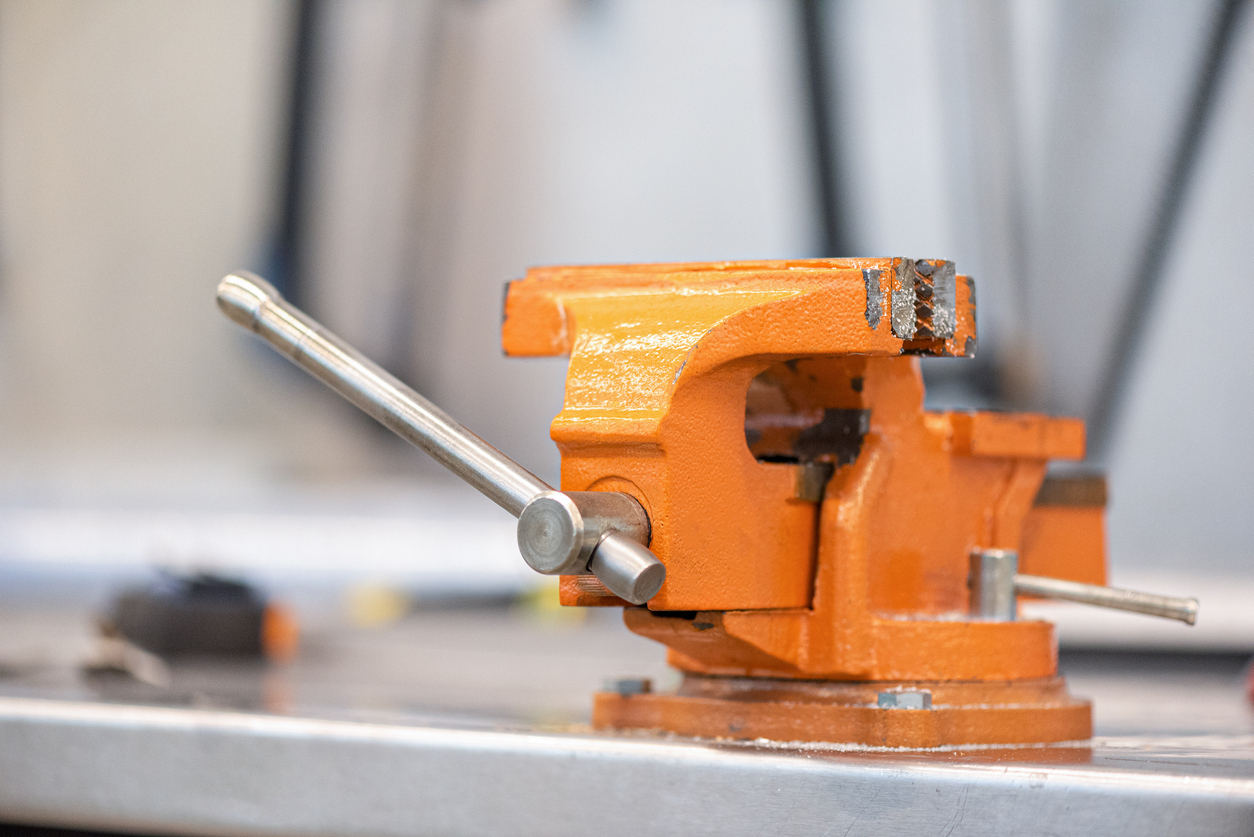

This heavy-duty device is mounted on the benchtop, bolted to its surface. It weighs as much as an anvil and in fact, may even function as a hammering block now and again as many models have a flat surface behind the jaws designed for use as an anvil. The engineer’s vise is also called a bench vise or a machinist’s vise, or sometimes a mechanic’s or railroad vise.

The primary purpose of a machinist’s vise is to grab hold of things and to hold them steady in its rough jaws, freeing up both your hands so that you can bend, shape, hammer, cut, drill, or perform any number of other operations. The jaws of the vise usually have a machined face that can easily scar wood. Some models these days are sold with reversible jaws that are smooth on one side and serrated on the other. If you have frequent need of a metal vise and only occasional need for a wood vise, you may buy jaw liners. Many machinist’s vises also have pipe jaws located beneath the main, flattened jaws.

The base on many machinist’s vises swivels, accommodating a variety of workpieces presented at different angles.