We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

A good handsaw, when properly treated, is a tool that can be passed with pride from one generation to the next. Essential to proper treatment is storing the saw correctly, in a place where the blade is protected and the atmosphere isn’t too damp. An occasional wipe with a rag dampened with machine oil is good for the blade, too.

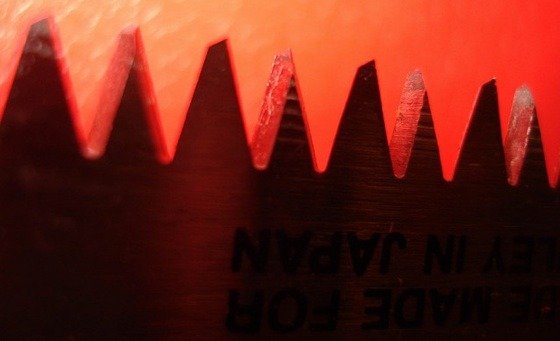

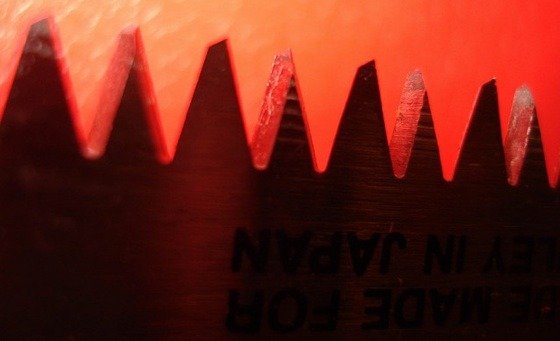

Over time, however, the best of handsaws, even those that are treated with proper care, get dull. The millions of collisions that the teeth experience in cutting wood both dull them and reduce their amount of splay (called “set”). The saw will begin to cut more slowly (because the teeth are dull) and tend to bind (because the set has narrowed).

Fortunately, it doesn’t take a magician to sharpen a handsaw. A little time, the proper tools, and a couple of simple techniques will restore that blade’s cutting edge.

The Tools

You’ll require a saw set for resetting the teeth, and a taper file or two. Both saw sets and taper files come in different sizes, so you’ll need to determine the number of teeth per inch in the saw (or saws) you will be sharpening, and use a set and file that are appropriate to it.

Inspect the Saw

Remove any rust from the sawblade using fine sandpaper or a wire brush. Look closely at the teeth: Are they all the same height? If not, you will need to perform an operation called jointing. Simply clamp the saw in a vise, using wood blocks as a backboard to hold the spine of the saw rigid. Then file the teeth until they are of uniform height. Use a double-cut, smooth metal file for the job, clamping it to a piece of scrap in order to keep it square to the saw blade.

Setting the Teeth

This step is necessary to make sure that the kerf is the proper width: Teeth that are out of alignment, regardless of their sharpness, will cut unevenly. The saw set makes this job a bit less painstaking, and ensures a more uniform set to the teeth.

The saw set resembles a pair of pliers, with a pair of long handles at one end, a small pair of jaws at the other, and a pivot in between. At the jaw end there is a rotating disk that, when turned, adjusts the travel of the tool, meaning that the plunger and anvil mounted on the jaws are closer together (or farther apart) when the handles of the tool are squeezed. When the set is then positioned against a tooth to be set, the tool will bend the tooth to the precise angle required for that size of saw.

Setting a saw can be done with-out a special tool but it’s not easy. Each tooth needs to be bent from its midpoint, and all the teeth must be bent evenly; the bend must be no more than half the depth of the tooth; the set on each side must be identical. I’d recommend if you’re going to go to the trouble of sharpening your own saws that you invest in a saw set.

To use one, you start by adjusting the saw set to conform with the number of teeth per inch on the saw, which may range from as few as four to as many as sixteen (saws with more teeth are probably best taken to a professional). Starting at one end of the saw, position the saw over the first tooth that is bent away from the tool’s handles. Then squeeze the handles… and the tooth is set.

Skip the next tooth (it’s set in the opposite direction), and repeat the process, working down the length of the saw, setting every other tooth. Try to exert the same pressure on the grip to achieve a uniform setting. Then turn the saw around and do it all over again with the other teeth that are set to the opposite side.

Filing the Teeth

Taper files range in size according to the tooth sizes they are intended to sharpen. The smallest files will sharpen saws with fine or coarse teeth, but the larger files will sharpen the larger- toothed saws more efficiently. There is some argument as to whether single-cut or double- cut files are best (either will do), but for coarse (five to seven points or teeth per inch), a regular taper is suitable; for medium coarse (eight to ten tpi) use a slim taper; for medium fine (eleven to fourteen) an extra-slim taper; for fifteen or more, a double extra- slim taper.

Whatever the size of the taper file, the shape is the same, as the file, in profile, is an equilateral triangle, meaning that each of its three angles is sixty degrees. This also means that the file will simultaneously file both the front of one tooth and the back of the one facing it, leaving them both shaped to the proper angle.

Clamp the saw, blade up, between two straight pieces of hardwood stock in a wood vise or purpose-made sharpening vise. The clamping arrangement should grip the sawblade close to the cutting edge, with the gullets (the troughs between the teeth) not more than a quarter of an inch from the jaws, to ensure that the blade is held rigid.