We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

So you’re in the market for a new furnace, maybe because the old one is hopelessly inefficient, or because Hurricane Sandy flooded your basement, or because you’ve decided to switch fuel types. Or maybe you want a unit that will make less noise. There are many reasons to scrap an old furnace, and just as many considerations to make when buying a new one.

Your first job will be to educate yourself about the options. That way, when you call in an HVAC contractor, you’ll understand the language. Knowing that you need a new “furnace” won’t cut it.

In fact, depending on your home’s heating system, “furnace” could be a misnomer. Furnaces heat air. If your heating appliance heats water, then it’s a boiler. If your appliance sources heat from the air, the ground, or a water reserve (such as a well or pond), then it’s one of several types of heat pumps.

Fuels vary too, of course. Furnaces and boilers may be fueled by oil or gas, or by propane, while heat pumps are typically powered by electricity (although new gas-fired and hybrid units are also available). An “electric furnace”—an electric strip heater in an air handler, that is—runs exclusively on electricity. On the other end of the spectrum are fireplace inserts and solid-fuel stoves, furnaces, and boilers, which use wood, pellet fuel, or coal.

Whatever heating appliance you choose must be matched to your home’s method of heat distribution—so again, it’s important to know what you have. If there are ducts and registers through which warm air blows, then you have forced-air distribution. If you have baseboard radiators, your distribution system is hydronic (hot water). If the heat comes from your floors (or walls or ceiling), your home relies on a radiant heat distribution. Yet another type, convective distribution, relies on the natural movement of air.

If you’re buying a new furnace, it’s a good time to consider changing your distribution system as well. Just be forewarned that doing so will add significantly to the cost of the overall project. Plumbing is never inexpensive, especially when long runs are involved. Finding spaces in which to run new ducts isn’t easy either. You may have to sacrifice a closet or run ducts from an attic space into the rooms below. Some clever carpentry is often required.

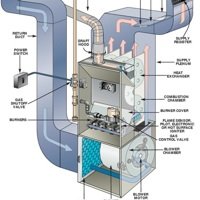

The Sum of its Parts

Your heating system can be defined as the combination of your heating appliance and your method of heat distribution. Numerous combinations are possible. One common permutation is a gas-fired furnace paired with forced-air distribution. This type of system delivers somewhat dry heat, can operate unevenly and noisily, and is subject to heat loss through ducts. But such systems easily accommodate central air conditioning–a big plus for many homeowners—and their cost is relatively low.

Gas- or oil-fired boilers are used as the heat source for radiator and baseboard hot-water systems. These produce a more comfortable heat but are more expensive than furnaces and do not accommodate air conditioning.

Radiant floor heating is likewise known for comfort. A typical setup is comprised of tubing (installed beneath flooring) through which circulates warm water that’s been heated by an oil or gas boiler. For small areas like bathroom floors, electric-resistance cables or heat mats might take the place of hydronic tubing.

A hydro-air system is part hydronic and part forced air. In this type of system, either a gas- or oil-fired boiler heats water that is pumped through a heat exchanger. Air blown through the heat exchanger is consequently warmed and distributed through ducts. Conveniently, the boiler in a hydro-air system may be used for heating domestic-use water, thereby eliminating the need for a separate water heater.

Yet another popular choice is the air-source heat pump. Once only an option in moderate climates, advances have made this technology suitable in colder regions as well. Air-source heat pumps run on electricity but are more efficient than other electric heaters, since they draw heat from the outside air, even when it’s fairly cold. When it gets a bit colder though, electricity is required (expensive!).

Heat pump-heated air is usually distributed to rooms via ductwork, but ductless heat pumps, called mini splits, are another option. A mini-split system involves one or more wall- or ceiling-mounted unit that blows warm air. The nice thing is that, when several units are running simultaneously, each is able to be controlled separately, so you can adjust output in different rooms as needed. The not-so-nice thing is that each unit must connect, through pipes or tubing, to an outdoor condenser/compressor. Many heat pumps, ductless included, can run in reverse during the summer to supply cool air.

The same pump technology that works with air actually works even better when drawing heat from the earth or a water reserve—in either case, temperatures are fairly consistent (45 to 65 degrees Fahrenheit, depending upon your climate). A ground-source heat pump (GSHP) operates efficiently in almost any climate, and it, too, can supply warm air in winter and cool air in summer.

One more heat pump-based system, a hybrid, marries an air-source heat pump with a gas- or oil-fired furnace, allowing fossil fuel to be used when air temperatures plummet and the heat pump ceases to be efficient. The system switches from one mode to the other automatically.

Folks typically end up replacing an old heating appliance with one of the same, or a similar, type. Some exceptions: When the homeowner wishes to change fuels, add central air conditioning, create extra space with a compact boiler, or relocate heating equipment. (New compact wall-hung boilers, called combi units, have no tank and can fit in a closet or hallway.) Obviously there are lots of choices, and if you’re replacing your furnace, there’s no better time to consider making other changes to improve your heating system.