We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

Barrier-Breaking Black Architects

Wikimedia Commons via Bluedog423

Though often hidden in the shadows, Black architects have been influential in architecture since the 1800s. These trailblazers had to overcome racial discrimination, segregation, a lack of professional opportunity, and other obstacles to achieve success. Some even designed structures that, because of segregation, they were forbidden to enter. Yet these men and women persevered to help shape America and pave the way for today’s Black architects.

Walter T. Bailey (1882–1941)

Wikimedia Commons via Zol87

The first African American to graduate from the University of Illinois School of Architecture, Walter T. Bailey also became the first licensed African American architect in the state. In 1905, he was appointed the head of the architecture department at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, where he also designed several campus buildings. He is best known for designing the renowned National Pythian Temple in Chicago, an eight-story Egyptian Revival landmark that was completed in 1927 and demolished in the 1980s. In 1939, he completed work on the First Church of Deliverance (pictured), which still stands in Chicago and was designated a landmark in 2005. Both structures served as symbols of African American achievement and power on Chicago’s South Side, in an area known as Black Metropolis, now called Bronzeville.

Robert Robinson Taylor (1868–1942)

flickr.com via kmariam3

The son of a slave in Wilmington, N.C., Robert Robinson Taylor became interested in architecture while working as a construction foreman. In 1888, he became the first Black student to enroll at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where he studied architecture in a program that was the first of its kind in the United States. After graduation, he became the first accredited African American architect and was later recruited by Booker T. Washington to design the campus buildings at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, one of the first institutions of higher learning for African Americans. The Oaks (pictured) was designed by Robert Robinson Taylor, built by students, and the former home and president’s office for Booker T. Washington.

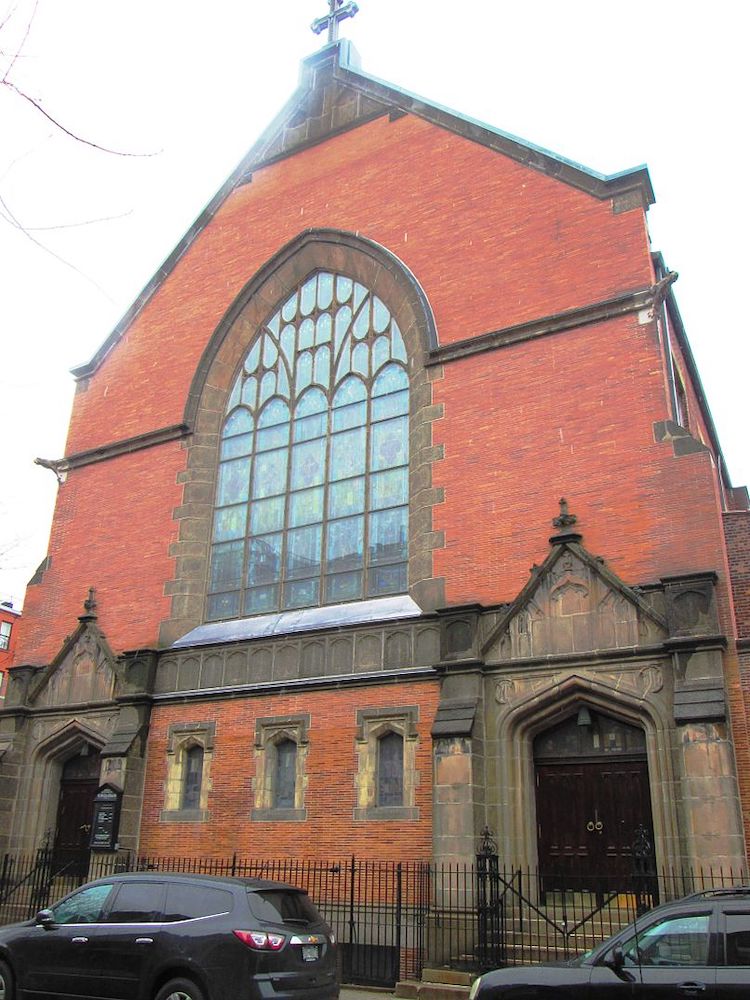

Vertner Woodson Tandy (1885–1949)

Wikimedia Commons via Beyond My Ken

Vertner Woodson Tandy learned the keys of his craft by watching his father, a brick mason, build homes in Lexington, Kentucky. Tandy began his formal training in architecture at the Tuskegee Institute before transferring to Cornell University in 1905 to complete his studies. There, he became a founding member of the first African American Greek letter fraternity. After graduation, he set up shop in New York City, where his completed projects include St. Phillip’s Episcopal Church in Harlem (pictured).

Julian Abele (1881–1950)

Julian Abele was an accomplished architect who lived in the shadows, his name absent from prominent blueprints of the Philadelphia firm he worked for, Horace Trumbauer. Abele graduated in 1902 as the first black student in architecture at the University of Pennsylvania. With the financial backing of Trumbauer, his future employer, he then traveled through Europe and studied at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris, which greatly influenced his later designs. He officially joined Trumbauer’s firm in 1906 and advanced to chief designer three years later. Abele took over Trumbauer’s firm after his death in 1938, spending much of his later career designing more than 30 buildings for the Duke University campus in Durham, N.C., including its chapel (pictured), library, and stadium. Duke did not desegregate until 1961, so even though Abele designed many of its buildings, he would not have been able to attend.

Moses McKissack III (1879–1952)

Wikimedia Commons via Andrew Jameson

Moses McKissack, along with his brother Calvin, founded the nation’s first Black-owned architectural firm, McKissack and McKissack. The craft is in the family’s blood, passed on by McKissack’s grandfather, who learned the building trade as a slave. The firm lives on even today, under the leadership of Deryl McKissack, the fifth generation of the family to continue the tradition. Moses McKissack III landed his first major commission in 1908, for the construction of the Carnegie Library at Fisk University in Nashville, which led to many more projects throughout the state. During President Franklin Roosevelt’s administration, McKissack received an appointment to the White House Conference on Housing Problems.

Beverly Loraine Greene (1915–1957)

Wikimedia Commons via UNESCO @ Paris

The first black female architect licensed in the United States, Beverly Loraine Greene studied her craft at the University of Illinois. After she graduated in 1937, racism made it difficult for Greene to find employment in Chicago, so she moved to New York City, where she worked on the Stuyvesant Town project. Ironically, Greene herself would not have been allowed to live in this post-war housing complex, which was initially racially restricted. She went on to receive her master’s degree in architecture at Columbia University and worked alongside many other notable architects, including Marcel Breuer, with whom she collaborated on the headquarters of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Unesco) in Paris (pictured). When she died in 1957 at the age of 41, she was working on several buildings for New York University, which were completed after her death.

William Sidney Pittman (1875–1958)

Wikimedia Commons via Renelibrary

Born to a former slave in Alabama, William Sidney Pittman began his journey in the field of architecture by assisting his uncle, a carpenter. Though Pittman’s formal preparation began at Tuskegee Institute, he moved on to the Drexel Institute (now University) in Philadelphia, graduating in 1900. He then returned to Tuskegee to head the school’s architectural drawing department and work as an assistant professor. He later moved to Washington, D.C., where he became the first African American architect to open his own office and also married Portia Washington, the daughter of Booker T. Washington. He designed many prominent buildings in Washington, D.C., including Garfield Elementary School and the Twelfth Street Young Men’s Christian Association Building. Pittman later moved to Texas and designed the Allen Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church (pictured). Not long after moving to Texas, however, he began to have trouble securing work, in part as a result of the racial segregation of the time, but also because of his eccentricities. He finished out his career working mainly as a skilled carpenter.

Clarence Wesley “Cap” Wigington (1883–1967)

Wikimedia Commons via McGhiever

If you have ever been to Saint Paul, Minn., then you have surely seen the work of Clarence W. Wigington, who designed many of the city’s municipal structures. Sixty of his buildings are still standing today, including the historic Highland Park Water Tower (pictured), built in 1928. He was the first African American registered architect in Minnesota and is believed to be the country’s first black municipal architect. He became well known for designing elaborate life-size ice palaces for the Saint Paul Winter Carnival.

Paul Revere Williams (1894–1980)

Wikimedia Commons via Dave Kirkeby

Paul R. Williams broke racial barriers and overcame personal challenges to become an accomplished architect who over a lengthy career designed more than 3,000 structures in a variety of styles. His projects ranged from homes for Hollywood stars like Cary Grant, Lucille Ball, Frank Sinatra, and Lon Chaney (cabin pictured) to highly regarded civic and commercial buildings. His best-known project is the Theme Building at Los Angeles International Airport, a space-age icon completed in 1961 and designed with the firm Pereira & Luckman. In 2017, he was posthumously awarded a prestigious gold medal from the AIA, making him the first African American to be given this honor. Successful though he was, it is said that he learned the skill of drawing upside down so he could sketch across the table for white clients who were uncomfortable sitting next to an African American.

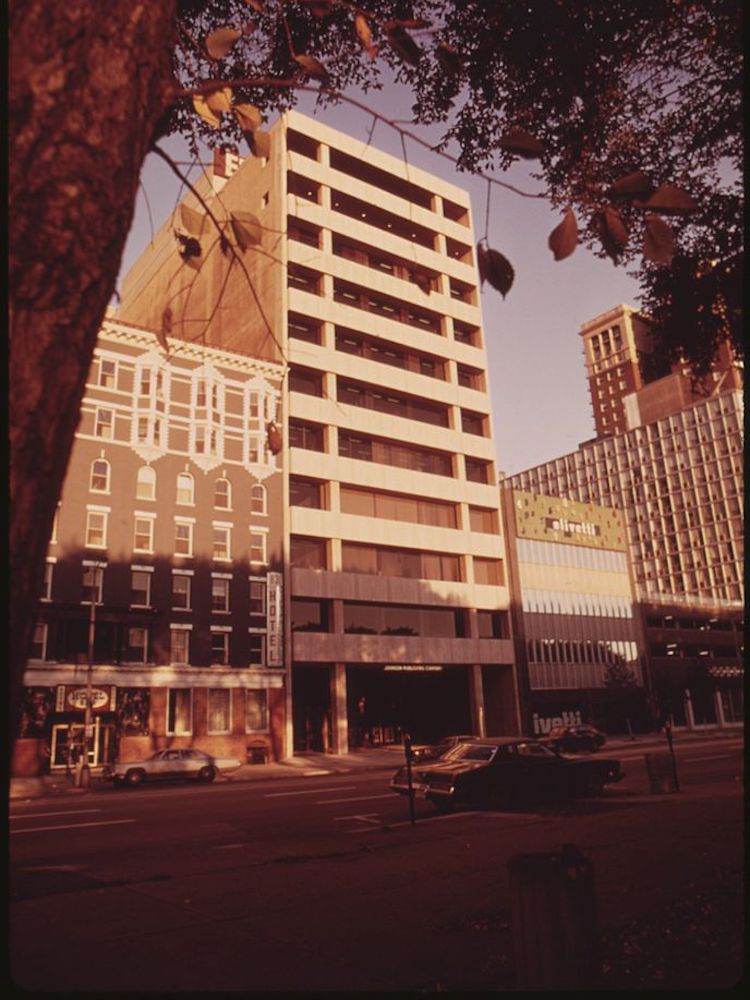

John Warren Moutoussamy (1922–1995)

Wikimedia Commons via U.S. National Archives and Records Administration

John Warren Moutoussamy learned his craft at the Illinois Institute of Technology, where he studied under architectural pioneer Mies van der Rohe. In 1971, he became the first Black architect to design a high-rise building in Chicago. The tower (pictured) served as the headquarters of the well-known Black-owned company Johnson Publishing, popular for the magazines “Ebony” and “Jet.” “It was a beacon, literally a beacon of hope,” said artist Raymond Anthony Thomas, a former Johnson Publishing art director, of the building’s importance to Black history and culture. Among other notable accomplishments, he became a partner in a major architecture firm and served on the board of trustees of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Wendell J. Campbell (1927–2008)

Wikimedia Commons via TonyTheTiger

In perhaps his greatest mark on the industry, Wendell J. Campbell cofounded and served as the first president of the National Organization of Black Architects in 1971. The group was later broadened and renamed the National Organization of Minority Architects. He studied on the GI Bill with Mies van der Rohe at the Illinois Institute of Technology, but after graduation he had difficulty obtaining work as an architect. As a result, he dedicated much of his time to urban planning and became passionate about urban renewal and affordable housing. He eventually started his own firm, Campbell & Macsai, an architectural urban planning company. The firm’s notable projects include overseeing the extensions and renovations of the McCormick Place convention center, the DuSable Museum of African American History (pictured), Trinity Church, and the Chicago Military Academy at Bronzeville.

J. Max Bond Jr. (1935–2009)

J. Max Bond Jr.’s architectural career spanned many miles and embodied Black civil rights and culture. After graduating with a master’s in architecture from Harvard in 1958, he was unable to find work in the United States, so he began his career in France under the French modernist architect André Wogenscky. He later worked in Ghana and Tunisia, eventually returning to the United States to found the successful firm of Bond Ryder & Associates, which went on to design the Martin Luther King, Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change in Atlanta, the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute in Birmingham, Alabama (pictured), and the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem. He also held prominent positions in education and city planning in New York City. As one of his final projects, he designed the museum section of the National September 11th Memorial & Museum at the World Trade Center.

John Saunders Chase (1925–2012)

Wikimedia Commons via Leijurv

After earning his bachelor’s degree from Hampton University in 1948, John Saunders Chase became the first African American to enroll in and graduate from the University of Texas at Austin School of Architecture, in 1952, shortly after the Supreme Court ruled to desegregate professional and graduate schools. He later became the first African American licensed to practice architecture in the state of Texas. In 1980, President Jimmy Carter selected him to serve on the United States Commission on Fine Arts, the first African American to hold this honor. Chase cofounded the National Organization of Minority Architects (NOMA) to recognize the contributions and promote the work of people of color in the field. The George R. Brown Convention Center in Houston, Texas (pictured), is just one of the impressive buildings designed by Chase’s firm.

Norma Sklarek (1926–2012)

Norma Sklarek was the first African American woman to become a licensed architect in New York as well as the first to become a member of the American Institute of Architects (AIA). She graduated from Columbia University with a degree in architecture, one of just two women and the only African American in her class. After graduation, her race and gender made it difficult for her to find employment. She was rejected by 19 firms before finding a position with the New York Department of Public Works. In 1950, she passed the architecture licensing exam and went on to work with the prestigious firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. During her career, she managed many prominent projects, including the Pacific Design Center in Los Angeles and San Bernardino City Hall. She was also notably the cofounder of one of the nation’s largest woman-owned architecture firms, Siegel Sklarek Diamond. Sklarek has been called the “Rosa Parks of architecture” for her accomplishments. The U.S. Embassy in Tokyo, Japan (pictured), was designed by Norma Sklarek in partnership with Cesar Pelli.

Robert Traynham Coles (1929–2020)

Wikimedia Commons via Pubdog

Like many of the other architects on this list, Coles was discouraged by his teachers from pursuing a career in architecture. Fortunately, that didn’t stop him, and he went on to earn a Bachelor of Architecture degree from the University of Minnesota and a Master of Architecture from MIT. In 1994, he became the first African American Chancellor of the American Institute of Architects (AIA). His works include many large-scale projects, such as the Frank D. Reeves Municipal Center in Washington, D.C., the Ambulatory Care Facility for Harlem Hospital, the Frank E. Merriweather Jr. Library in Buffalo, the Johnnie B. Wiley Sports Pavilion in Buffalo, and the Alumni Arena at the University of Buffalo. His modest home studio is pictured.

Everything You Need for a Lush and Healthy Lawn

Keeping your grass green and your plants thriving doesn’t just take a green thumb—it starts with the right tools and supplies.